An effective knowledge-management strategy begins with the goal: application of knowledge to advance high-quality, equitable service provision. Working backward from the system’s ambitious goals, learning leaders set, maintain, and enact the vision for how the data and information generated in learning spaces turns into knowledge that can be used to achieve organizational goals.

This work is grounded in a key equity principle: All knowledge is democratic. Learning leaders decentralize knowledge ownership. They engage all stakeholders, particularly those closest to the work, in the generation, consolidation, sharing, and application of knowledge. All stakeholders—including staff, students, parents, and community members—have the opportunity to not only give input but also meaningfully contribute to decisions about which ideas are worth capturing and scaling. Democratic participation strengthens knowledge generation and builds buy-in and capacity for knowledge application, yielding better and more efficient outcomes.

Learning leaders act on three knowledge-management drivers to advance transformation at scale. They:

Adapt and adopt a knowledge-management approach

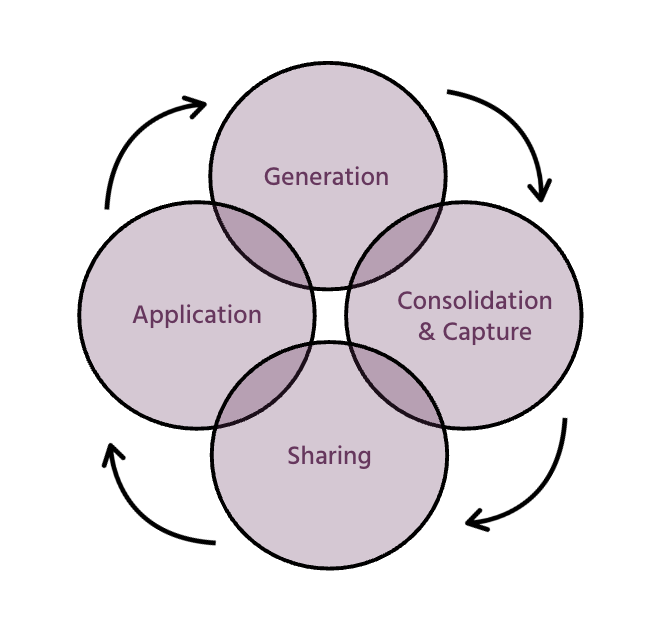

Knowledge management is the set of processes used to create, organize, share, and use knowledge in an organization. Learning leaders use a knowledge-management framework consisting of four interconnected phases to make use of learning at all levels in order to continually improve. These phases include:

- Knowledge generation: Data and information are uncovered or generated.

- Knowledge consolidation and capture: Generated data and information are turned into knowledge.

- Knowledge sharing: Captured knowledge is communicated to others.

- Knowledge application: Shared knowledge is applied to make decisions and improve practice.

Architect a comprehensive knowledge-management system

With a strong understanding of the characteristics of each phase of the knowledge management cycle, learning leaders design and refine the processes and routines that make up their knowledge-management system. Many components of the system may already be in place. Usually these include the learning spaces where knowledge generation happens (e.g., short-cycle testing routines) and the repositories that store captured knowledge. The challenge facing most learning leaders is how to create a comprehensive system that links the knowledge-management phases so that the improved knowledge of each individual and organization is applied consistently.

To architect a comprehensive knowledge-management system, learning leaders revisit the overall structure of their system, ensuring it is set up like a dynamic network and coordinated learning community. They minimize silos and organize individuals in teams and clusters that are bridged through high- and low-density ties that support knowledge spread and application. They also devise processes to detect and act on deficiencies in their existing knowledge-management systems and to embed knowledge-management routines and structures into daily operation.

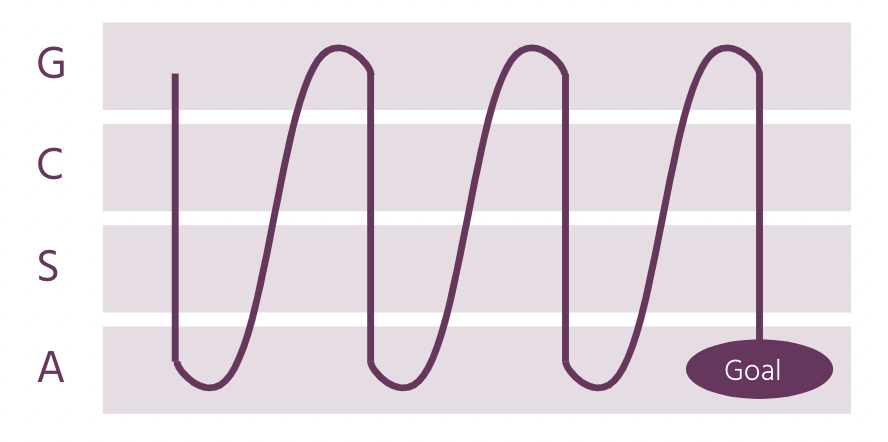

The cycles of a mature knowledge-management system look like waves when captured in a process map, with each knowledge-generation activity followed by aligned consolidation, capture, sharing, and application processes. Full and linked knowledge-management “waves” accelerate improvements at scale.

Cultivate a culture that supports knowledge management

Designing and implementing the infrastructure to move knowledge through a system so that it advances more equitable outcomes is critical, but it cannot be sustained without a set of shared conditions and organizational commitments.

As they cultivate these conditions and set these commitments, leaders commit to democratic principles. They actively engage diverse stakeholders in the practice of learning, and in doing so they ensure that knowledge identification is the responsibility of every community member. This commitment to democratizing knowledge differs from other organizational structures in that it rejects the notion that knowledge belongs to those with positional authority or recognized expertise. A robust knowledge-management cycle can uncover tacit knowledge from those closest to the work and encourage innovation and buy-in to the development of novel solutions.